We Got the Power

84 artists, 113 pieces

October 11–December 20, 2024

The CAMP Gallery

The opportunity to co- curate the sixth (!!) edition of the gallery’s legacy exhibition is an incredibly special one because the very first edition is the one that sparked my interest in pursuing a career in curating. I was fresh out of undergrad and I was debating how viable working in a gallery was—I’ve always understood the cultural capital of it all, but after being given a chance to cut my teeth, as it were, I suddenly found myself feeling like I’d finally found just where I was meant to be.

Back then it was eight artists, though, and I wasn’t jurying or heading the logistics of the exhibition either, let alone figuring out who would share which spaces on the gallery walls. I’ve worked on every edition of this exhibition, and though it hasn’t ever passed without new grays sprouting atop my gorgeous curly head, it’s always been satisfying.

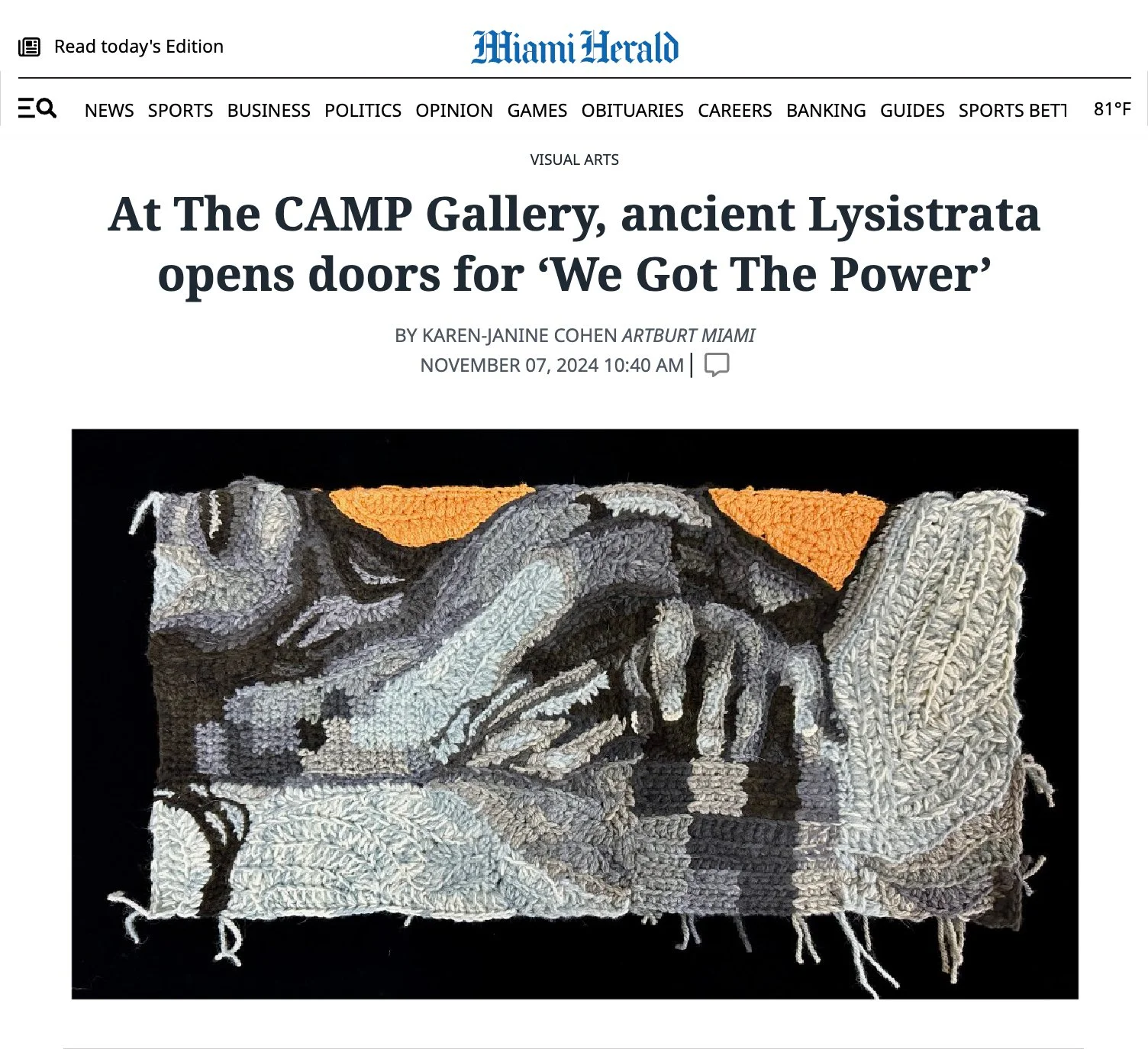

There’s something thrilling and grounding about being able to connect EIGHTY-FOUR unique perspectives without a hitch, and I believe that this is because of the innate qualities of textiles. As cultural markers, the techniques and general accessibility of textiles give us permission to break away from the boundary between “fine art” and “consumer,” and reframe our relationships with art-making in general. In addition to this, the installation of these 113 12 x 24 inch panels prove that visible and imagined differences don’t keep us from true connection. In fact, they make it possible.

The intention of the comedy, Lysistrata, by Aristophanes (412 BCE) is not the intention of this exhibition, 77 Women Pulling at the Threads of Social Discourse: We Got the Power.

Aristophanes a Greek playwright known as the Prince of Ancient Comedy, wrote Lysistrata nineteen years into the Peloponnesian War. As a person who was culturally responsible for engaging within the spheres of ideology as well as highlighting their fault points with a unique perspective, he naturally mirrored his society's values and ideas. Like a great deal of artists across history, he wasn’t fighting in the war.

So with this in mind, it’s incredible to think about his proposing to the Greek masses that the ongoing forever-war could be resolved by women 2,612 year ago. Women, the very part of societies all over the Earth that not only make up a great deal of the collateral damage during war, but are made responsible for their communities’ survival whether they're considered fabulously or otherwise. However, this is not what Aristophanes was doing. In Lysistrata, Aristophanes mocks women while exposing himself, or his attitudes at the least, and the ideological space in which he and his brethren consider them. He proposes something silly: a woman giving up sex despite the fact that this is what she’s good for (in a hetero-patriarchal context, anyway.) It's reflexive of the binary, rather than a delicate duality, that Aristophanes and his contemporaries capitalized upon in their reflections of society, war and peace, and being.

A contemporary, critical position on this play may leave us wondering if these are still truly the only resources fully available to us. Sex, love, withholding, manipulation; a corporeal game of intellectual-sexual chess. Is this the only context in which to consider ourselves as powerful? Given the present, persistent criminalization of sex work, and outcasting of those who rely on it for survival, the journey to an answer is murky at best. The play’s titular character, Lysistrata, shows us that this plague unto itself is built into Western culture when she laments the full, albeit sparse spectrum of choices available to her.

The Contemporary Art Modern Project’s interpretation, like many modern and post-modern interpretations, centers a markedly non-male, intersectional gaze. How do we arrive here in the face of this, in some ways, offensive reference material? How do we take a duplicitous and super ancient echoing of those visions and values and derive such a display? How do we go from the violence and harm inherent to misogyny, sexism, disenfranchisement—and a downright alienating male attitude that won’t quit—to a showcasing of the power of authentic unity, deliberately contextualized outside of it?

Perhaps we can start to reframe Lysistrata as radical, headstrong, and desperate; a woman with the moxie, guts, and, yes, balls to make change happen no matter the cost. We can also note the fact that Lysistrata and her “No Peace, No Pussy” (footnote, Soriano 2024) posse are not after domination. Men, in a great deal of contexts, tend to view and employ sex as a tool, a weapon for control. The Lysistrata crew is after peace, by any means necessary, and they’re taking ownership of what they can do by reassessing their lack of access as the perfect catalyst.

77 Women Pulling at the Threads of Social Discourse: We Got the Power is predominantly made up of artists who identify as women, with wonderful exceptions of course, all of whom have a stake in the balancing of progress and preservation by any means necessary. The artists in this exhibition have contributed artwork with an interest in acknowledging their shared cultural responsibilities as peacemakers and civic players. This collection of narratives encompasses a variety of ages, gender identities, technical knowledge, and cultural experiences through an emphasis on textiles and fiber. They weaponize the pliability of and incorrect presumptions about the medium in what is a testament to the power of reframing and, notably, reconstructing ideas we may have internalized about what we are and are not good for. Much like Lysistrata, the artists in this exhibition tuned in to where collective resolve can catapult us beyond collateral damage—up, through, and out of the despair.

The phrase “we got the power” is nestled in the title of this exhibition as a sober assertion. Lysistrata understands that where her oppression ends is exactly where her liberation blooms, and that like thread, it’s a mechanism made to connect segments that have either split apart or been categorized as different from the start. And, while Aristophanes didn’t intend for this kind of subversion, his perfectly imperfect unmasking of the true nature of systems of domination is the perfect needle.

Each of the 110 artworks on the walls have been deliberately placed edge-to-edge to form segments of an ancient Greek frieze, an elaborate, manual effort in adorning classical structures. However, this installation, its purpose, and thus Aristophanes’ entry into the fossilized narratives kept alive in the Western canon, brilliantly disassemble ideologies of powerlessness. This soft frieze allows what are considered stories of collateral damage to overflow. We Got the Power, like Lysistrata, exemplifies exactly how war, violence, slaughter, and distortion are not where we should find power and greatness.

The concept of peace relies upon a challenge to redefine the historical lens through which we engage with the present, and a unified construction of our shared future. In the place of obliterating one another within the ideological battlegrounds of our cultures, the artists in this exhibition center play, joy, honor, truth, and an acknowledgement that survival isn’t simply in the hands of whomever is afforded agency and power. The creativity of the eighty artists whose ideas populate the walls of our intellectual playground grants them an extraordinary access not simply to power, but advocacy for those who have yet to self-actualize. They’re capitalizing on the expectations for art-making as peace-making as Lysistrata capitalizes on her presumed duty. They use what they know they are good for to guide us in a creative reassessing of how we view and understand ideologies we have every right to disrupt for the benefit of our societies’ survival—and legacy.

Co-curated with Melanie Prapopoulos

Statement by Maria Gabriela Di Giammarco